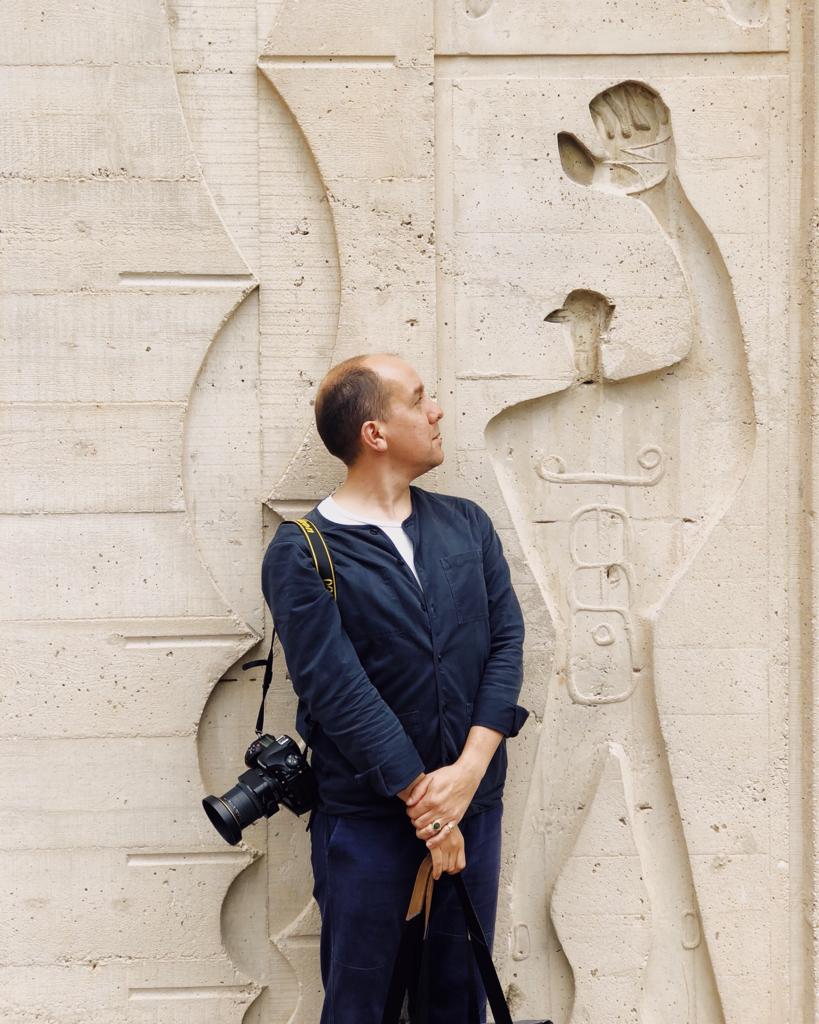

Jim Stephenson

Spurred by a genuine love for buildings, Jim Stephenson (AKA Clickclickjim) has been fortunate to forge a successful career combining two of his favourite pursuits: architecture and photography. Growing up with an architectural engineer for a father lent him a certain level of exposure and understanding of what makes a great building. But it’s his experience as a previously practising architectural technologist that truly informs his work. Here, he tells us how he manages to capture our human connection to bricks and mortar with the mediums of still photography and film, and how serendipity had a hand in landing him his cherished career.

I never set out to be a photographer. I was interested in it as a hobby when I was a teenager but then it was really just taking photos of friends. I was completely obsessed with buildings. My dad was (and still is) a one-man-band architectural engineer and he worked from home, so I grew up with trace paper and drawing pens around the house, and joined him on building sites. He mainly does residential work, barn conversions etc., and I started working for him when I was around 15 or 16; making copies of drawings initially, then doing planning drawings, then technical drawings, and eventually being on site with small projects by the time I was 18. I went to university in Brighton to study Architectural Technology, where I had to work in the industry for a year, so I went to America and worked for a small practice in New Hampshire. My boss there was a keen photographer and once told me that if I can spend months and years designing a building, I should at least know how to take one good photograph of it, and that really stuck with me. I came back, got my degree, worked for some practices in the UK and did in-house photography alongside the drawing I was doing.

In 2008, when the industry went into meltdown, I was made redundant. Nobody in architecture seemed to be hiring and the only other job I had experience for was shop work, but all the shops were shutting down so that was a dead end. I was in my mid-late 20s and didn’t have any savings, so had to find a new way to make some money very quickly. I realised architects were having to work harder to win work during the recession, so they were still commissioning photography. Virtually overnight, I set up as a photographer. The first few months were just about paying the rent, and it all built up from there. I always thought it’d be temporary to be honest, and I’d go back into practice once the recovery from the recession began but now I can’t imagine doing anything else.

After a while, I realised that the switch in professions wasn’t quite as big as I thought it would be. Really, I’d just swapped pen and paper (or CAD package, more accurately) for a camera and I was still doing what I wanted to – exploring architecture and the built environment. The exploration is ongoing.

I think my background inevitably has a big effect on my photography, but it’s hard to quantify because I don’t know any different. From a practical perspective, I still have just about enough memories of working in practice to be able to have meaningful discussions with clients about the design, technical aspects, influences etc. They can brief me in the language they’d use to describe a project with a colleague, then it’s my job to translate that for a broader audience in images and video. There’s a more haptic influence as well I think – an understanding of what material choices and texture do to a work of architecture. How a building’s use can be bent by public engagement and how to notice that. I think an education in architecture makes you look at buildings differently, just as training as a chef would make a trip to a restaurant different.

It’s definitely changing as I learn and develop more. I’ve found more recently that architects are commissioning me specifically because they want photos of their work with people in, which is great because that’s what I love to do – document spaces being occupied and used. Most of my work has some sign of life in it – often that means people in the images, but equally it can be more subtle. Even without a human figure, some ‘controlled mess’ in a new home gives the viewer a subtle sense that something happens there and it’s not a museum piece held in aspic. I like a bit of mess to be honest – I think my work is a little looser than most architectural photography. Although I shoot a lot of my work with tilt shift lenses with the camera waiting on a tripod whilst I move furniture around to get the everything looking right, I also photograph hand-held a lot, with a smaller lighter camera. At least half the photos from any shoot I do have been taken like this.

I like the projects with strong haptic qualities. Textures and an interesting play of light – ones that have shadows as well as sunshine. For me, the best kind of commission is something I would have liked to have worked on as a designer, projects that are well used and/or open for anyone to experience; schools, galleries and museums, and even better, social housing or community projects, where you have to work in a different way to photograph the life of the space as well as the structure of it.

At least half my work is moving image these days, and while the subject matter remains the same (architecture), there’s a growing interest in that area from architects and press outlets. I’ve made nearly 200 short films in the last couple of years, about various buildings around the world and it’s a wonderful way to tell a story.

At their cores, stills and film are pretty similar. I use the same cameras for both and I compose in a broadly similar way. When I’m doing a shoot that is only stills, I’m trying to tell a story with a collected set of images (the story of the building) but with a film, that sense of storytelling takes on a different dimension. You get to create a self-contained narrative, with interviews and sound and movement. The edit, the arrangement of the shots, becomes really important as we try to keep the viewer engaged with what the film is showing them. The sound, whether it’s the ambient sound around the building, music or a spoken voice, adds a huge amount of texture, and movement, either the movement of the camera or the movement of people in the frame, adds depth and a sense of life. Essentially, with the films I do I’m trying to create a cinematic space – a recreation in their mind for the viewer of the building and what it feels like to be there.

I try to do all that with a photoshoot as well of course, but with film it’s a bit more direct as it’s all self-contained and the individual shots can’t be extracted and moved around, taken out of context or shown on their own in the same way as they can with a set of photos.

I don’t think of film as an alternative to photography, I think it’s just another useful way to tell the story of a building to a viewer. For some people photos will be the most engaging medium, for some it might be text and for some it might be a short film.

Have you seen the portraits Tyler Mitchell took of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez? It was for Vanity Fair and there’s two against large fabric backdrops that completely stopped me in my tracks. What he’s doing right now is amazing – his activism and passionate engagement through the medium of photography is really what being an artist is about. He’s also only 25 I think, and he’s already making waves in the industry. His book, I Can Make You Feel Good, is at the top of my ‘most wanted’ list.

Chris Killip’s work is huge for me, particularly the Skinningrove images. Until recently, I ran a monthly photography lecture series and we had photographers from all over the world come and do talks for us, so I’ve hundreds of names I could reference for this question! I’ll tell you who I really look forward to seeing in my Instagram feed right now (in addition to Tyler Mitchell): Annie Collinge’s work always makes me smile; Gordon MacDonald and Clare Strand’s work ‘No More Flags’ is well timed; Peter Clarkson’s street photography is beautiful and cinematic; and Juann Bremmer’s work from Guatemala is ace.

Also, he’s not a photographer (in the traditional sense), but I’m a big fan of Roger Deakins and the podcast he and James (his wife and longtime collaborator) do offers a great insight into cinematography.

Riga in Latvia was a big highlight – I was commissioned to spend four or five days photographing a theatre installation by long time clients and friends, TAAT (Theatre as Architecture Architecture as Theatre). The shoot came in the middle of a really busy and quite tricky run of work and I hadn’t had the chance to stop and be excited about the trip. Once I arrived there, I fell in love with the place though. And the people I was working with were great as well. The work I do for them (which is usually at arts and theatre festivals all over Europe) is the most collaborative work I do for anyone. And for them, the process of building the installation is as important as the finished thing, so I get really embedded in the projects they do. It’s also intense work, but so much fun.

There’s a lot of places (like Riga) that I’ve visited for work, enjoyed and vowed to return on holiday. Seoul and Singapore were both really exciting but too fleeting, but equally I love working in the UK. Any chance I get to go to Liverpool or Scotland is eagerly taken, and anything in the countryside makes me happy – I do a lot of work with Invisible Studio in the woods near Bath.

It’s really about spending the time observing how people interact with the building, so on a shoot I will spend some time before I start photographing just watching the space. This is especially important in public buildings like museums and galleries, but also relevant to houses and homes as well.

Whenever possible I try not to pose people, or ask them to perform a particular task. In a public building that often means watching and waiting to see how people are interacting with the building and each other. Sometimes (in a train station for instance), it’s more about the movement through the building and sometimes (as in a museum) it’s more about the moments where the people have paused and have a more direct interaction.

In a home I don’t try to have a person in every shot. That sense of inhabitation comes from the objects and ‘mess’ you see in the photo and I save the photos with people actually in them for spaces like the kitchen or living areas. In those spaces I speak with the residents before the shoot starts and ask them what time they might be making lunch or dinner or something like that and I make sure I’m there for that.

Most of my work falls in to two types of images – the ones that give information and the ones that give atmosphere (and the two occasionally crossover, of course). The information images tell the viewer about materials, scale, decoration, the type of room, how it’s used and so on. The atmosphere images are just as important though. They might be less architectural in subject matter; they might focus more on a texture or the way the light is falling on something, or an object that expresses the homeowner’s personality. They’re the ones that give the viewer a sense of what it’s like to be there. They’re the meat to the bones provided by the information images, so it’s important not to forget them as well.

I really like photographing homes that are used in unusual ways. One of my favourite shoots was a house by Loyn + Co Architects that I photographed for The Architects Journal years ago as the owners were artists, so half the spaces were studios. So, I suppose an ideal shoot would be the home of an artist who lived in their studio. I bet Sonia and Robert Delaunay’s home in Paris was spectacular – she incorporated so much of her own work (and her husband’s) into the house.

Sofia and I live in Brighton & Hove in a late 60s housing block. It’s a beautiful building. I’ve been in Brighton for 20 years now and this is the third flat I’ve rented in this block! The rooms are well-proportioned, as you’d expect from that era and it feels really solid. The decor of the rooms is dominated by the fact that Fi can’t stop buying books, so we have bookshelves everywhere (some donated by our friends and neighbours, the furniture designers Baines & Fricker). We have similar, but slightly different tastes so I think our home is a reflection of both of us living here as two people together, but with different personalities. At times it’s quite eclectic but always better for it.

Sofia is studying an MA in Photography and we share an office in the flat, which occasionally is a peaceful haven for us to work in, but mostly is a messy cacophony of our camera equipment, books and test prints. We also have a couple of cats who somehow manage to be loved, but also the bane of my life at the same time.

Remember that being able to take a really good photograph is only one part of being a photographer. Make sure people know you exist. In 2008, when I was starting out, that meant going to events and meeting architects, cold calling and taking my portfolio to see them, but these days it’s more about having an active Instagram page and engaging with discussion online. If nobody knows you exist, nobody is going to commission you.

Be easy to work with. Don’t be a walkover of course, but don’t get a reputation for being difficult either – when I worked in practice I was in meetings where architects would discuss photographers to commission and they’d dismiss names out of hand on the basis they didn’t like the experience of working with them, even if they took good images. That always stuck with me.

I’ve just finished editing a new film with Piers Taylor and Sarah Wigglesworth all about her life as an architect and we’re really pleased with it! That will be available to watch online early 2021.