The spirit of the place: the transformation of two barns on the Isle of Wight

Words by Hannah Nixon

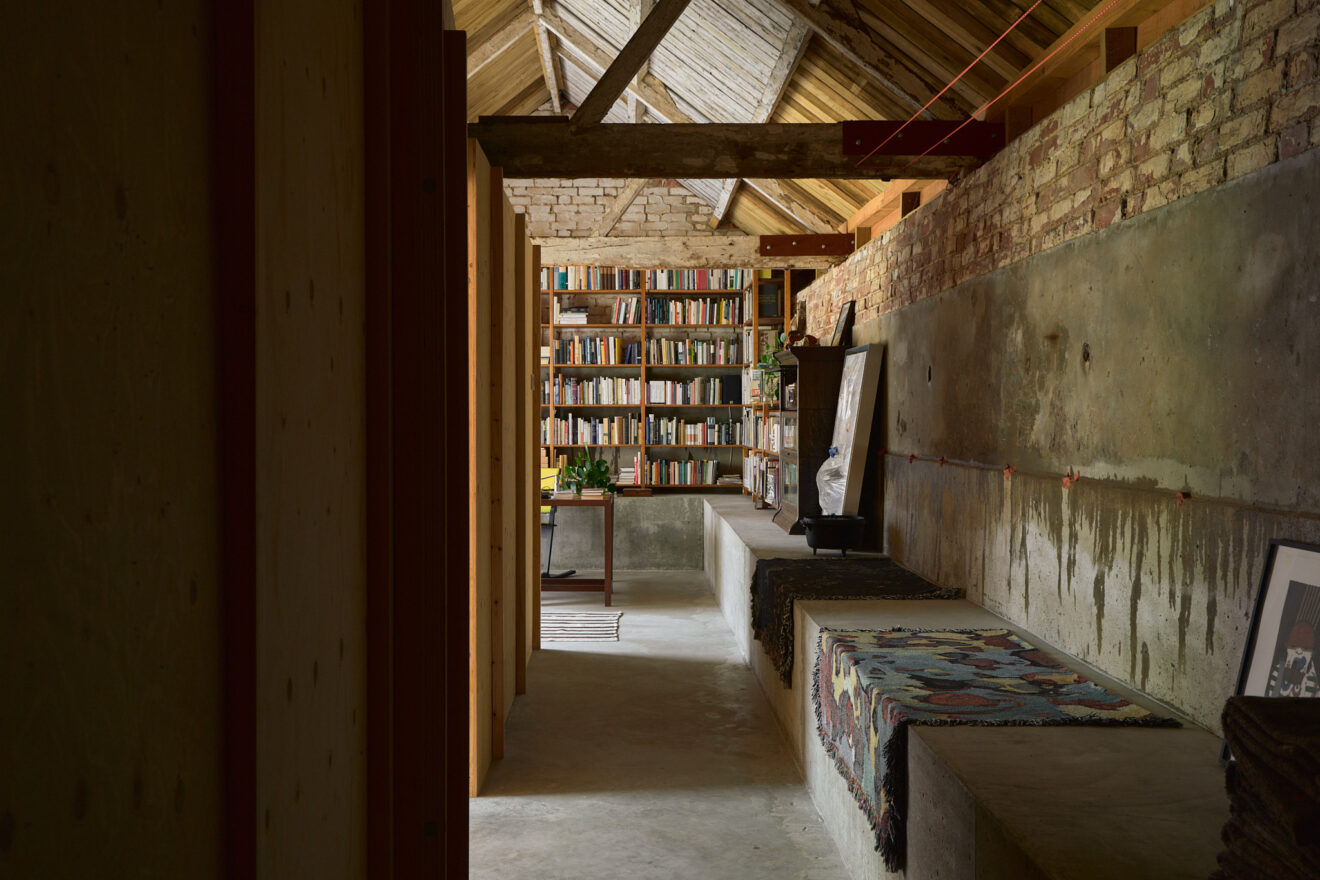

The approach to The Old Byre is as unassuming as they come. A winding country lane leads past two donkeys grazing lazily in a nearby field, before a glimpse of corrugated cement board signals the presence of an industrial building. This modest exterior nods to the ethos behind owner Joseph Kohlmaier’s long-nurtured passion project and is the result of a fruitful collaboration with architect Gianni Botsford, whom he first met decades ago. Inside, the building’s philosophy unfolds: two barns renovated to form a domestic space along with an open-door policy for fellow artists, its vernacular character demonstrated by the pocketholed brickwork yet enriched by modernist touches, from polycarbonate panels wrapping the barns to soaring glazed doors.

There’s a dualism that runs through the project; the twin barns, public and private spaces and at the heart of the build, the relationship between Joseph and Gianni. When asked about his first impressions of the barns, Gianni recalls how the site was a “hidden, secret little world.” He goes on to say, “it was always very easy working with Joseph because we just understood each other. He supports the process and making everything as good as we possibly could. All those kinds of things make a big difference.”

We stayed with Joseph to film the exceptional and singular space, which has won three RIBA awards including the RIBA National Award 2025, and learned about the genius loci he found on a mud heap, magnetic doors and the beauty of turning a building ‘inside out’.

I was looking for a place to buy or maybe a plot to build on, but with no specific agenda. I saw some images of these barns and I told the children, “I’ll be back in an hour.” I drove here and let myself in. The cows were out, but the doors were open. I could look into the courtyard and see the interior space. I stood on a deep layer of muck and I thought, ‘This is so beautiful’. (laughs) There’s something really wonderful about this place. I don’t know what it is.

The way all these buildings met each other, they’re all from different centuries. It all formed this extraordinary genius loci – ‘the spirit of a place’. I couldn’t really understand at the time exactly what it was.

I had a very concrete interest in architecture that I developed in my early thirties. I was a graphic designer at the time. We [Joseph’s business partner] were working for an architecture school designing all their collateral. One day I received a letter from one of the professors, a very influential person for me, the late Bob Harbison who said, we’re starting this new MA in architectural history, theory and interpretation. So he sent more information and I replied, “This is great – and can I come for an interview?”

I felt that the way the course looked at architecture as a conduit to think about everything; politics, society, life, the body, healthcare, you name it. That’s what architecture is essentially. I met lots of architects, fellow students, but also teachers. I met Gianni Botsford, the architect of this house, back then too.

At the same time, I’ve always loved making things. I went to a very progressive school, between the age of 16 and 18. I learned how to blacksmith and work with wood, so I’ve built lots of the kitchens that I’ve lived in. Making things and thinking about making things in a much broader, social and philosophical context go hand in hand for me.

We [Joseph’s business partner] made Gianni’s websites, I think we made three. So we’ve been working together as a team for a very long time. I know how Gianni approaches architecture and we connected on a personal level. I saw how Gianni goes about approaching questions and this idea of starting from nothing, which is also present in a lot of my work. You work with what’s there.

Of course, architecture is built on precedent, but there is a way of refusing the precedent. Gianni’s approach is very much about finding a place and its context, getting to know the environment and the people that are involved. It’s working slowly through these conversations, making endless models and working with existing materials. Making sure that the design evolves through this process is what really interests me. I thought he was the right person for this project, because that’s how I wanted this particular building and project to evolve.

It doesn’t have to be other buildings or projects, just situations you’ve been in that inform your vision and Gianni’s. These two visions become connected and entangled in a strange way. For example, this idea of turning a building inside out. Rather than leaving the façade as it is and insulating the inside, doing things the other way around. There are precedents for this: Kate Darby, who works with Gianni, lives in a house where they did something very similar to an existing ancient barn. When you’re in space, you still see the old walls and you see the bird’s nests. I have two here.

The polycarbonate façade that we used facing the courtyard is used in cultural or industrial buildings, from car parks to the Trinity Laban Center in London. Everything that you see here has some connection to something we’ve seen before. But it wasn’t the process of bringing all these precedents together like in a collage, and shall we do this or that? It was a material palette, and a way of doing things that have existed in many other different contexts.

There’s an undone quality to the finishing of the building. I like particularly where some of the old brickwork has corroded over time. It allows you to see the cross section of the materials and it’s quite nice to understand how the space has been made comfortable.

I like this idea of a diagram that you look into the layers of the building. It’s not just about creating a wall or a surface to hang a picture on, but it’s about exposing different stories or different levels of the history of this building and leaving them as they are.

It also makes the house indestructible! If I drill a hole and hang a picture, if I take it off I don’t have to fill the hole, it makes no difference whatsoever. Things can age and can be used and break off and be fixed again. Essentially what you see is what was here. It means that when you’re in it, you’re not consciously looking at it like a museum. I often say animals used to live here and now we live here; just a different sort of form of creature.

It’s always a challenge to connect old and new things. There’s always difficult junctures or contradictions. It can be frustrating, but generally it somehow works in the end.

Structurally, the barns were very old. The 19th century barn, where I now work and sleep, needed underpinning. We couldn’t access the wall from the street, so we built a bench that holds the wall up, and that has become part of the design. So many of the things that you see have emerged out of pragmatic decisions, and that’s what’s beautiful about them. They weren’t put in place because it was the perfect solution, it was just what had to be done in order to make the place work and then that became part of the character of the building. But the process was really quite straightforward.

We’re not far from the mainland, generally, it’s not a problem. Sometimes, you need to plan ahead if you want a specific special material. But that hasn’t really been a problem either. There are some really good building companies here; it’s a very industrious and creative place.

In a way, the Isle of Wight chose me. My children grew up here and I’ve lived on and off the Island for almost 17 years. Once you get to know the island, you see it has had lots of strange histories and they’re all still palpable in a way. Queen Victoria built a Tuscan style palace that she absolutely loved, the Bloomsbury set came and hung out here, painting and writing poems. Alfred Lord Tennyson had a property on the west side.

It’s also a shifting population with people from different backgrounds. There’s also lots of young people here who do interesting things like make sustainable clothing, etc. Famously, Wet Leg came out of the Isle of Wight. It is an island and yet totally connected.

Traditionally, when you have an old farm building, you’d clean it up and fix the façade. This building is the other way around. The interior was left as it is and the outside was insulated. The way it presents itself to the landscape has changed, although it looks quite anonymous just like any other barn building, the interior is where all the history, the purpose of the building and the life the animals had is preserved. It’s completely the other way around.

The doors are really crazy, aren’t they? They’re like sails in the wind. You have a door that essentially feels like it’s part of the walls. So when they’re closed, the door is almost not there. The builder came up with the idea of using magnets to close the doors. You don’t have a lock, but you get this sense of pulling, and when you open it, there’s a little bit of resistance.

For many years I had a public teaching space at the university, which was an open seminar room, but it had my private library in it with lots of my objects. It was loved as a teaching space by my colleagues because it wasn’t sterile, it had someone’s private possessions, but they were also public. Books are like ships, not really something you own.

The story of this library, you can transpose onto the rest of the building; this is a private home, but at the same time, there is a public aspect to it. That philosophy has informed the way the building was designed; this idea that other people could come here and be transformed. That’s what makes the place conducive to work. It’s calming as well as stimulating.

People who come into the space tend to generally be surprised by what feels like a domestic space, but at the same time appears to be something else. That seems so different and yet it works. There have been comments about the fact that you can really feel that this is the outcome of an interesting, friendly, and productive relationship between people who made this place what it is.

So much of what I think about this place has emerged as a byproduct and it’s very hard to put your finger on it. The personality of this house is connected to my personality, but also to the personalities of all the people who were involved in its making and people who’ve been in my life.

I can just remember sitting on a chair the first time we cooked here; it was already a nice place to be despite there being nothing in it. It’s obvious that these walls feel like they have a history. That means you are surrounded by something that is speaking to you. It’s not neutral. I think that is what makes it so special and beautiful.