John Pawson – the way he lives now

We speak with architectural designer John Pawson, master of the pared-down aesthetic, about a change of pace, the rituals of entertaining and why everyone should get involved with architecture.

Spartan, pared-down, minimalist – these are all words that have been used to describe the work of British architectural designer John Pawson. He refers to it, rather poetically, as ‘traveling light’. Was he always this way inclined? “I’ve got four older sisters and they always thought I was a bit weird. I remember my sister Diana, the youngest one, sent me – after I’d got going and done a bit of work and had an office and things – she sent me this note with a blank piece of paper saying, “I enclose my application for membership to the minimalist club,”” he laughs. “She was one of the early jokers.”

Pawson hails from strong industrial stock, with a long lineage in textiles. “My father’s family had a textile business for a few generations and he could feel your jacket and tell you exactly what weight the fabric was. My mother’s side were in textiles, too, but she was a genuinely modest person in every way even though her family had done well: her dress, the way she conducted things – she had one or two trumpet outfits, but it would be a Chanel suit she wore all her life, which was very reassuring.”

Growing up in industrial Halifax certainly left its mark. “The landscape and the industrial buildings, playing in those non-conformist chapels – something rubbed off,” he reflects. As did the discovery of great architects who were to influence Pawson all his life. “Learning that there was someone out there called Mies van der Rohe who brought buildings to their absolute most, most essence – sort of perfection really. I mean the absolute definition of minimum is Mies van der Rohe, where you cannot add or subtract an object – that it’s reached its perfection in the Farnsworth House, or the Siedlung building or Barcelona Pavilion. To discover Mies as a teenager was just amazing.” The world of architecture and design was to broaden Pawson’s horizons, quite literally. From the pages of Domus Magazine, he learned of architect Shiro Kuramata – “a contemporary, living version of Mies, really” – and this discovery spurred him to leave Halifax behind for the quiet zen of Japan, where he met his hero. ”I was chasing a 16th century Japan, it was schoolboy stuff. I thought I was going to arrive and everywhere was going to look like a zen temple – of course, it didn’t. Contemporary Japan is just as exciting, but it’s a mess of overhead wires and noise. Of course those beautiful monasteries exist if you can get away into the mountains, but there’s always a tourist group round the next corner.”

But today Pawson really does seem to have found his pocket of peace in a tiny hamlet in rural Oxfordshire, though a place in the countryside was his wife Catherine’s idea. Pawson, on the other hand, took some convincing. “I never wanted anywhere outside of London because it took me thirty years to get to London. I was in Halifax until I was 24 and then I didn’t even get to Tokyo in Japan, I got to Nagoya – I never got to a metropolis! So by the time I was 30, I’d finally ended up in London and I never wanted to leave. But Catherine had this idea of a bolthole in the countryside, where we could escape to at the weekends – a lock-up-and-go tiny cottage. I wasn’t really interested until she was sent the particulars through about a disordered and run-down farmyard and she said “Well this is exactly what we don’t want.””

This “run-down farmyard” Pawson refers to is Home Farm. A cluster of 17th century farm buildings now fashioned into one beautiful dwelling resplendent with carp pond, orchard and breathtaking bucolic views of the surrounding 24 acres of Cotswold countryside. Pawson saw its potential instantly; “It was an amazing view – it had its back to an escarpment. It was up the hill and looked down on the low valley, so I could see there was opportunity for a series of different spaces, different volumes – a lot of variety. Of course it was a mammoth undertaking but that’s what I do – usually for clients with deeper pockets,” he adds self-effacingly. “Catherine was horrified. It was gigantic to her, but having done the monastery in the Czech Republic, it was a tenth of the size. We got our monastery in the end.”

The monastery Pawson is referring to is The Abbey of Our Lady of Nový Dvůr – an exquisitely designed space for an order of Trappist monks, located in a remote part of Bohemia. There is indeed a touch of the monastic about Home Farm; soaring vaulted ceilings, lime plastered walls and a distinct lack of the superfluous (well, obviously). The Grade II listed original cottage dating back to 1610 and its slightly younger add-on have been knitted together with the stable and barn to create a home spanning 50 metres long. “We’ve filled the gap between the cottages and the stable and the barn and I opened them up from north to south, so you can see the whole 50 metres of the buildings.” Huge swathes of glazing – including an enormous floor-to-ceiling sash window in the triple-height barn kitchen that slides up to allow the outdoors in – invites quiet contemplation and serves as a tranquil spot to sit and watch the seasons shift around you. “It’s almost like a calendar or a slow movie or something.” Inside is a blend of contemporary and traditional materials in calm colours that hang beautifully on the ancient bones of the building: terrazzo and elm, marble and cotswold stone. With 66 windows in total, Pawson was eventually coaxed by his wife into having curtains made. “I wasn’t sure and she said, “Well, there’s this wonderful undyed boiled wool which is very similar to what the Cistercian monks wear, it’s from Lyon” – so we’ve got the curtains in that. It’s my first experience with curtains,” he laughs. “Not too many, not all the windows!” Similarly, the bedsheets are selected for their plain modesty; “very thick off-white linen sheets but they’re unpressed – not creased exactly, but a bit like when they first come off the roller. They’ve got some sort of body to them, which is very nice. She’s careful to fit them to the house – they’re what I would choose if I had the expertise.”

Pawson is full of praise for his wife of 32 years, Catherine. “She’s the most amazingly calm, even-tempered and wonderful person to live with.” She’s also the perfect foil for his spartanism. “She worked for (British heritage fabric and wallpaper company) Colefax and Fowler, so she’s used to pattern. Although my background is in fabrics and textiles, I’ve gone the no-frills route. So it’s been fantastic to have Catherine’s eye and expertise for all the soft bits.” When it comes to hiding household clutter, Pawson happily admits he’s countered again. “It’s not a zen buddhist monastery. I’ve got three children and a wife I love, and family has always come first for me. We’ve got a grandson, Bert, and he’s immaculate, a joy. And his toys are rather wonderful to have all over the place – I’d much rather have that than an empty house. I like to see order and I like the effect when you tidy up – but for Catherine that’s not important, she doesn’t fuss about that kind of thing. She’s a very, very good cook, so the kitchen can become slightly disordered, but my job is washing up!”

And with no less than three kitchens, that could be quite a task. Three kitchens might seem a little out of step with Pawson’s no-frills approach but it transpires that the idea was born out of practicality rather than (heaven forbid) excess. “We wanted to be able to use the barn as a proper living space and it needed a kitchen because it’s a long way from the farmhouse. But the farmhouse kitchen is very nice in winter – and there’s a cart house with a hay loft above, that has a kitchen in, too. They’re really three self-contained units that can be used as one.”

Despite the imposing footprint of the house, all the rooms are in use regularly, though you do get a sense that there’s something of a seasonal rotation in play: the cosy farmhouse kitchen in winter with its fire lit; the airy barn kitchen with its huge window thrown wide open towards the carp pond in summer. Pawson and his wife battened down the hatches with their adult children during last year’s stretch of enforced confinement. “We’ve had the year at Home Farm, and it’s been such a privilege to live here with our grown-up children. The three kitchens have definitely been a huge plus – there hasn’t been one argument or bad temper the whole year.” Home Farm has fortuitously proved to be quite the playbook for lockdown living, with its unique configuration also fluid enough to accommodate Catherine’s family for a socially distanced gathering after her mother’s funeral earlier this year. “We had four or five different family units and they were able to come back and to serve themselves in isolation. It was very flexible and quite surreal, actually.”

Family gatherings are hugely important to the Pawsons, particularly those that centre around food. “For both of us growing up, mealtimes were always very important. My mother was a very good cook and with four sisters we all had to sit down. Obviously there weren’t mobile phones in those days and we certainly weren’t allowed television during the meal, but Catherine and I have sort of continued that with our children. It wasn’t dictated, it just happened – a chance to get together and focus on each other and discuss things, it’s important.”

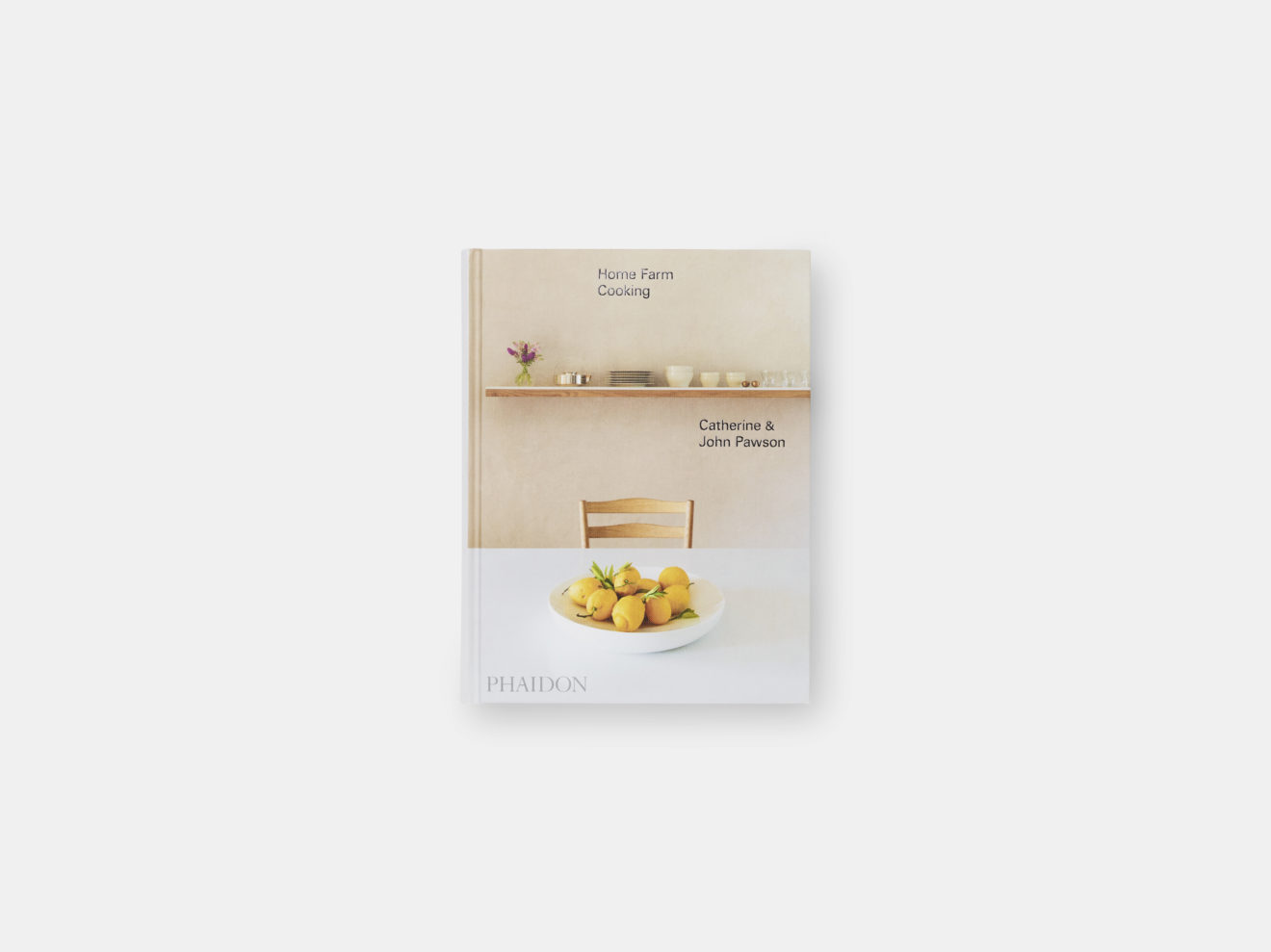

So perhaps a slight detour into cookbooks shouldn’t come as a surprise. Their recently published joint project, Home Farm Cooking (Phaidon), is a comforting mix of familiar and seasonal hearty fare. One hundred or so recipes the pair would normally whip up for family and friends (saffron chicken tagine, Piedmontese peppers, fish pie), and is as much about the savoured rituals of entertaining and the convivial immersive experience of sharing and enjoying a meal, as it is about delicious flavour combinations. It is, in fact, Pawson’s second cookbook (his first, Living and Eating, was co-authored with Annie Bell in 2004). “Catherine always said to me “I don’t mind cooking if you tell me what you want to eat” – and that’s how the first book with Annie Bell came up.” But arguably the star of the show in this second book is Home Farm itself, a glorious stage upon which to showcase their culinary delights. For Pawson, his foray into food is a natural extension to his work as an architectural designer, with the experience of being in a home and the daily rituals practised there being every bit as important as the structure. “I think people have always been a bit surprised that as an architect that I do other stuff. To me, the home is central to architecture – it’s centred round the hearth and food, and objects and furniture – it’s all part of what I would call architecture. Architecture isn’t just about the outside of buildings.”

These objects of the home that Pawson refers to are another string to his bow, having designed various homeware collections throughout his illustrious career: throws for Spanish textile company Teixidors; carrara marble vessels for Italian design house Salvatori; cutlery and kettles for When Objects Work and cook pots for Demeyere. Unsurprisingly, Pawson likes his dining table sparse. “I only like the minimum on the table, so for me it would be a glass for wine or water, a plate and a knife or fork, and then each time you bring what you need to the table. I don’t like flowers on the table, and personally I never really like salt and pepper – if you get the taste right you don’t have to muck around afterwards.”

So what does a gathering look like in the Pawson household? “When I was 70 in the summer before lockdown, we were able to seat 22 people at the table comfortably. We had that in the barn, that was wonderful.” His favourite dish to serve guests is nettle risotto. “It sounds bizarre but I love rice, because of being in Japan, and I love the shock and surprise of nettles tasting delicious. You’ve got to get them in the right season and the right place – you don’t want them too near the road.”

Despite his initial resistance, Pawson has thoroughly embraced life in the country. “The pace is much slower – there’s a lot of time to think and to watch the changes of the landscape. I kidded myself that I’d have a studio and it would be a great place to work, but in London I’m in a basement looking at a blank white wall and that’s much more conducive to work for me.” He’s relaxed when the subject of the future crops up. “I don’t know about moving forward. I’m driven, but not in the accepted ambitious way, I’ve just followed the stream, really, I never had a grand plan. I keep trying to get to the essence of something, pushing myself to get the design right. But it’s not the size or quantity and certainly not the recognition. People talk to me – I think it’s because I’m past 70 – but they talk about legacy and I’ve always had a resistance to keeping stuff. Of course the office stop me throwing things away. There’s a warehouse full of models and stuff which I wouldn’t have kept.” Interestingly Pawson never completed his studies in architecture, “it was just too long and too involved”, though he follows this with a caveat; “but I would always encourage anybody to get involved with architecture because it covers everything about our life doesn’t it? We have to have shelter, we have to have spiritual places. Whether we build them ourselves or not, we have to experience them. It’s not just about buildings, there’s lots of history and the appreciation of it and the writing, the photographing it – it covers everything. It can be as practical and engineering-like as you want, or it can be just art – I would always encourage people to go into architecture.”

John and Catherine’s recipe for Nettle Risotto:

This recipe is based on the nettle risotto I tasted at Skye Gyngell’s wonderful restaurant, Spring. Who would have guessed that this most vicious weed could make such a bright and tasty dish? Make sure to forage the nettles in early spring when the leaves are young and tender. Pick away from roadsides and wear gloves and use scissors to avoid being stung. Nettles can also be made into a highly nutritious soup.

Preperation time: 20 minutes

Cooking time: 20-25 minutes

Serves: 4

Ingredients:

– 1.5 kg / 3 1/4 lb nettles, washed with care in 2-3 changes of cold water

– 2.5 litres / 84 1/2 fl oz (10 1/2 cups) vegetable or chicken stock (broth)

– 100g / 3 1/2 oz (7 tablespoons) unsalted butter, half of it cold and cubed

– 2 shallots, finely chopped

– 400 g / 14 oz (2 cups plus 2 tablespoons) carnaroli risotto rice

– 125 ml / 4 1/4 fl oz (1/2 cup) dry white wine

– 90 g / 3 1/4 oz Parmesan cheese, grated, plus extra to serve

– sea salt and black pepper

– Wild Garlic Pesto (recipe page 068 Home Farm Cooking) to serve

Method:

Bring a large saucepan of water to the boil, add the nettles and blanch for 30 seconds. Drain but retain a little of the cooking water. Refresh in iced water to stop them cooking and retain their vibrant colour, then drain again and process in a food processor or blender with a little cooking water until smooth. Set aside.

Bring the stock (broth) to the boil in a saucepan, reduce the heat and maintain at a simmer.

Meanwhile, melt half the butter in a heavy sauté pan (keep the cubed butter for finishing the risotto). Add the shopped shallots and cook gently for about 5 minutes, or until softened but not browned. Add the rice and stir until the grains are coated in the butter. Pour in the wine and let it reduce right down. Start to add the warm stock, a ladle or two at a time, stirring gently as the stock is absorbed by the rice. Continue stirring and adding stock for about 15 minutes, then stir in the blended nettles. Keep adding the stock for a few more minutes until the rice is cooked – try little bit, it should be firm to the bite.

Remove the pan from the heat, cover and leave for a minute, remove the lid and stir in the cubed, cold butter and grated cheese. Season to taste and serve straight away with a small bowl of pesto and another of extra grated Parmesan.